"The dominant voice of militarized masculinity and decontextualized rationality speaks so loudly in our culture, it will remain difficult for any other voice to be heard... until that voice is delegitimated".

The article was initially published on Infocom.am.

This analysis aims to reveal the socio-linguistic features that are conditioned by war. The text does not claim to be in-depth research, but rather aims to show what the connection is between war, language, gender identity, and what additional layers there are for studying this topic further.

It is known that military rhetoric is based on the language of violence [2], and violence is closely linked to gender identity. Language is seen as a tool to rationalize and justify violence, including war, even if that war is undesirable for the general public. This interconnection is due to specific language-based thinking, control over an individual's behavior, views, and feelings in a given society, complex clusters of relationships and social relations, national ideology, and social structures based on human relationships that are constantly and dynamically evolving.

The "victory" of the Armenian side in the first Karabakh war (1992-1994) was romanticized through all the existing political and social institutions, and the criticism of the war and all the circles serving it was tabooed. The war discourse became the monopoly of men, and women, who carried the main economic and social burden of war, remained invisible and was silenced․ Did the last war change this situation? Does the defeat give an opportunity to reformulate the patriarchal war language and to reposition?

Media, Discourse and Silence

Media/social media has promoted to make women's voices more heard in recent years, particularly during the recent war, even if that voice is heard from patriarchal positions. During the war days, there were very few people who expressed anti-war ideas, made calls or posts in public domain, and as a rule, they were women. More often such discussions took place within the framework of "narrow" credibility and consensus.

If we try to systematize the texts spread during the war, we can distinguish between public and non-public texts, taking-a-stand and emotional/sentimental texts. It is not surprising that the latter type of texts prevailed in women's discourse. Women whose sons, husbands, or brothers were on the battlefield were unequivocally critical of the war in the private domain, wanting it to end as soon as possible. These criticisms, however, were almost or never voiced out in public. The public demand to stop the war as soon as possible was not heard, and the unresolved issues of regional and domestic security in Armenia contributed to the reinforcement of silence.

The fear/taboo of not speaking in public was first of all conditioned by a certain female solidarity, which supposed that after the end of the war there would be many mothers whose sons or other relatives were killed or wounded; and, they would a priori try to substantiate that those deaths were not meaningless and, consequently, the war was not meaningless either. On the contrary, "if the son did not die in the war, she has no right to speak"․ This was explicitly forced silence in our patriarchal society.

This mentality contributed to the active spread of calls for more militant warfare and birth of sons, both during and after the war. Were people making such calls actually ready to sacrifice their children/relatives to the "god of war", or was such a discourse unintentional, manipulative in nature, and aimed to serve the militarized policy of the state? In any case, we face the classic patriarchal approach, according to which a woman is a machine that gives birth to/produces a child/soldier, and a woman's decision to have or not to have a child is the monopoly of the state.

Social media also contributed to the fact that swearing became a "normalized" language for the Armenian society. During the war and after that, aggressive texts rich in swearing became widespread and entered the field of women's discourse. The latter began to use the language of violence and swearing widely, which was more evident in the comment section of media publications of politicians and the Azerbaijani Internet posts. This war showed to some extent that the language of women was de-normatized. It seems that such a change leads to the liberalization of women, but, on the other hand, the phenomenon has a significant energy of aggression and thus it deepens the masculine discourse in the society.

The Language of Symbolism and Commercialization of Women

Visual symbolism as a language is very often used in parallel with general rhetoric to create the image of politicians and public figures, as well as to make the message more targeted.

After the 2018 revolution, Anna Hakobyan (Spouse of the Prime Minister of Armenia) came up with the "Women for Peace" initiative, within the framework of which various discussions, courses on tactical basics were organized, and photos were published, on which the latter was shown in a military uniform holding flowers. This ambiguous message originally had a peace implication, but during the 44-day war it received a pronounced militaristic form. The topic was widely manipulated by the media and highly criticized after it became known during the war that Anna Hakobyan was in the bunkers of the Artsakh Defense Army. The majority of the society considered this step as a "dangerous public stunt", substantiated by the fact that a woman/Prime Minister's wife had no right to be in a strategic security facility. On the other hand, the event was negatively perceived by the anti-militarist civil society, which qualified such an act by Anna Hakobyan as a symbolic call for Armenian women to be involved in hostilities. This visual message may have been aimed at peace at first, but in terms of content it clearly defended the same patriarchal line and had a tendency to romanticize the war.

The appointment of Shushan Stepanyan as the spokesperson for the Ministry of Defense was an attempt of an interesting and positive message from the perspective of symbolism. However, this was not perceived unequivocally by the Armenian society, as her far more balanced informative messages during the war did not have the same impact on the society as the pathetic fallacious messages of the male spokesperson. On the other hand, it should be taken into account that the Ministry of Defense is the main institution formulating and serving the militarization, in which even the expansion of female staff does not lead to the demilitarization of the country and the society.

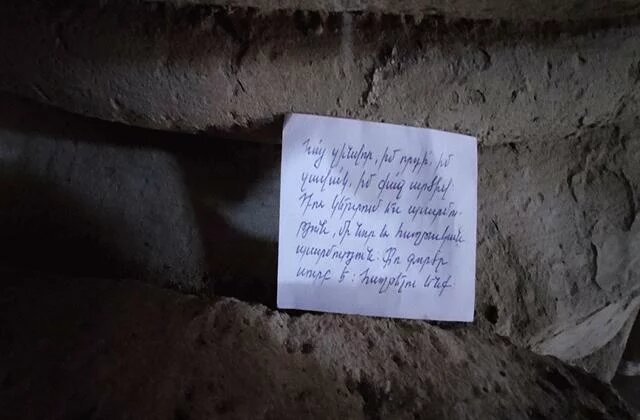

The involvement of women in this war was incomparably greater than before. The seemingly liberating component of the aforementioned phenomenon actually had another trickster side: by engaging in war, women became the bearers and multipliers of militaristic discourse. In addition, by being involved in this war at various levels, women also contributed to its commercialization by not being able to invent anything other than offering themselves as a reward for participating in the war. On the "Snickers" chocolates sent to the battlefield were written: "Hurry up and come home so that I can come from Moscow, and we'll have a handsome boy like you", "Come home, so that my children call you daddy", which were irrational, not always reflective, and were immediately caught by big entrepreneurs, using this circumstance to expand the sale of chocolate. This seemingly innocent, radically emerged initiative of Armenian women and other similar initiatives were called to serve the capitalism of war.

***

Thus, to sum up this brief overview, we can certainly state that a number of seemingly liberating phenomena, such as the de-normatization of language, the expansion of women's involvement in the war, the appointment of a female spokesperson for the Ministry of Defense deepen in essence the patriarchal and militaristic culture in Armenian society.

Talking about peace in our country is considered as a weakness/treason and recessive discourse, that is why it is often attributed to women. Unfortunately, during this war, even among women, it did not become dominant and publicly heard.

I thank Sona Manusyan, Lusine Kharatyan, Gayane Ayvazyan, Rima Grigoryan and Hamlet Melkumyan for exchanging ideas on this analytical text.

[1] Carol Cohn. Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 12 (1987): 687-718.

[2] Culture of Violence in Armenia, editor: G.Ter-Gabrielyan, Yerevan, Eurasia Partnership Foundation, 2020.